Chicken Soup for the Multicultural Soul

How did a simple broth become synonymous with comfort? Mimi Sheraton wrote in her The Whole World Loves Chicken that its medicinal origins can be traced back to a 12th-century doctor called Maimonides, who claimed that consuming the broth helped maintain the body’s balance.

Chicken is a near-universal ingredient, approved for consumption by most of the major faiths. Chicken is cheap and forgiving, generously lending flavor to stock, just as it has for generations. It is, perhaps, the great unifier in these troubled times: a soothing food, and one that brings together disparate communities. Regardless of the reason, it’s a perfect wintertime food.

The term “chicken soup” covers an endless array of dishes, and there’s a chicken soup recipe in nearly every cuisine. If your goal were to taste as many cultures’ examples of chicken soup as possible, you’d do well to begin your journey in Queens, where Mexican, Korean, Jewish, Burmese, Filipino and dozens of other cuisines cohabit in close quarters. Here’s a small sampling of chicken soups from five different cultures and where you can find them yourselves this winter.

Taqueria Coatzingo

Red. Mexican eatery Taqueria Coatzingo’s pozole rojo, the hot, deeply rust-colored compatriot of the milder green pozole verde, tastes about as fiery as it looks. Dating back to the Aztecs, the name pozole means “hominy”—dried corn treated with an alkaline solution—in the Nahuatl language. This particular bowl has a welcoming sharpness and acidity that pushes up playfully against the pleasant tingle of red chilies, and a spritz of fresh lime juice amplifies the soup’s sinus-clearing, eye-opening powers. The faint nuttiness of corn comes through every so often. Bits of vegetation, which the waitress informs me are hojas de aguacate (avocado leaves), float amongst bits of shredded chicken. Instead of sleepy, as chicken soup often renders me, I feel bright-eyed and awake, my cheeks the color of the pozole. I love the acid, the heat, the al dente bite of the hominy. The taste of chicken serves as backdrop, but a comforting and necessary one nonetheless.

Hansol Nutrition Center

The samgyetang at Korean restaurant Hansol Nutrition Center is nothing if not a show-stopper. Served in a heavy, hot stone bowl on a thick bronze plate, it’s almost ceremonial in presentation, hissing and crackling well into the meal. I slice through the tender boiled hen with a spoon to reveal a stuffing of glutinous rice, whole garlic cloves and a single jujube, or red date, fleshy and deeply sweet. Though not unctuous or salty, the soup tastes of the cartilage, fat, bones and skin of the chicken that gave itself to make it. Bits of fresh ginseng yield a medicinal tang. My father, savoring his bibimbap, remarks nostalgically, “My grandmother used to make boiled chicken.” As I learn from the manager Hoon, translated by our waiter, the soup is traditionally eaten on the first day of each of the three distinct summer seasons in Korean culture. Those are, it so happens, the restaurant’s busiest days out of the year, but the soup is good enough to eat year-round.

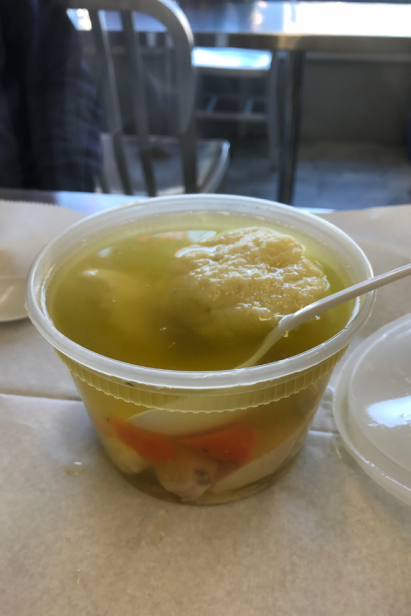

Knish Nosh

Ana Vasilescu, the chef of Knish Nosh, is as sick of being interviewed as she is proud of her recipes. Stout and blond, she is famous for the handmade knishes and chicken soup that are both increasing rarities these days. Her soup is a classic goldene yoich, or golden broth, with the requisite fluffy kneidlach, or matzo balls, and noodles. She eventually gives in to my questioning with an enigmatic smile. She learned to make the soup in Romania, her native country, but there were other influences, too—like the chef Jacques Pepin, of all people. She tells me she boils the chicken and vegetables for about an hour and a half, and then strains it—that’s the essential part—to remove the fat. “Nobody eats fat.” She even dunks the matzo balls in cold water to remove the oil. I’m none the wiser; the soup is lacking in nothing, and it tastes like the stuff my grandmother ladled out during the high holidays. Chef Vasilescu sends me off with a couple of extra knishes, tossed in the bag as goodwill.

Burmese Bites

As I ask Myo Lin Thway, owner and chef of Burmese Bites, about his ohno-kaukswe (Burmese coconut-chicken soup), he pulls, slaps and layers impossibly thin sheets of dough to make flaky Burmese palata breads, barely looking down as he does so. His technical prowess extends to the soup which, along with the whole of Burmese cuisine, is rare in New York outside of his pop-up at the Queens International Night Market, where I’ve come to find it. Salt, sugar and fish sauce get added to a broth made from whole simmered chicken, then the coconut milk, cooked down to develop its flavor. To thicken, gram (chickpea) flour gets added and noodles make it a meal. The salty murk of fish sauce gives it an addictive depth, though, as Myo tells me, “not everybody can accept” the smell of fish sauce. He tells me that in Myanmar it’s eaten any time of day, from breakfast to a midnight snack, which sounds heavenly. Like a painter’s palette, the soup gets topped with a small mound of bright red chili powder, a lime wedge, onion and chopped cilantro.

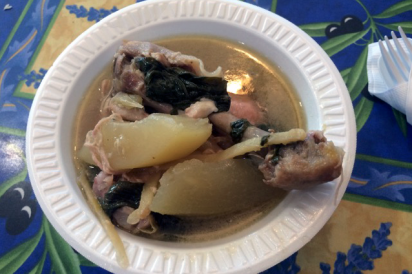

Manny’s Bake Shop

I stand at the counter of Filipino eatery Manny’s Bake Shop and, after placing my order of tinolang manok (Filipino chicken soup) with a tiny, stern-looking woman, she hands me a Styrofoam plate of white rice. I linger by the counter until, at last, I see her ladle a portion of cloudy-looking broth and a whole chicken leg (read: tender dark meat) into a small bowl. I sit and eat the hot rice saturated with savory liquid fowl, along with creamy chunks of some mystery vegetable that the owner Marlyn Hernandez informs me are green papaya, a fruit used in the Philippines like a vegetable. It’s like a potato on steroids. Marlyn tells me the soup is pretty much the same as it would be back home, with the exception of hard-to-find green pepper leaves, for which she substitutes spinach. She’s been here too long to really remember the difference, though. How long? “Thirty-two years!” A long time to be away.

Mimi Sheraton | @mimisheraton

The Whole World Loves Chicken

Taqueria Coatzingo

Hansol Nutrition Center

Knish Nosh

Burmese Bites | @burmesebites

Queens International Night Market

Manny’s Bake Shop