Gathering at the Table: Refugee Cooking on Lesbos

On a sunny afternoon in Lesbos, a Greek island 10 miles off the coast of Turkey, two women enter the kitchen of a small restaurant called to cook dinner. The food at Welcome Home is authentic Greek: pita bread with thick lemony tzatziki, salads of tomatoes and cucumbers dressed simply with olive oil, and fresh seafood served unadorned except for a wedge of lemon. But the food cooked today will be different. The two women, Ariane and Gallyn, are Cameroon refugees and their plan is to cook a communal African meal.

For the past three years, this small unassuming restaurant has been a unique gathering place for refugees. Owned by husband and wife Nikos and Katerina Katsouris, Welcome Home is staffed partially by refugees and hosts free communal meals. Some days it might be Nepali momos, meat-filled dumplings with ginger and coriander, or Syrian kebabs fragrant with the smell of parsley and pepper, all cooked by local refugees. Lesbos is at the forefront of the European refugee crisis. According to the United Nations, one million refugees have passed through Greece since 2015, with 45% of them landing on Lesbos.

Ariane and Gallyn enter the restaurant kitchen carrying several shopping bags filled with ingredients. On today’s menu is a West Cameroonian peanut stew with pork and beef. A West African country where French is the predominant language, Cameroon’s cuisine is one of the most diverse in the region, featuring influences from all over Africa.

The women begin by chopping whole cabbages along with tomatoes, garlic and ginger. Both meats are marinated in a potent mixture of garlic, black pepper and Maggi beef bouillon, before being boiled and fried. The smells are intoxicating. It’s so enticing that the Greek restaurant staff, despite being on break, are drawn into the kitchen by the delicious, unfamiliar smells. With no language in common, communication is relegated to satisfied smiles and enthusiastic thumbs ups. Good food requires no translator.

As the women cook, they explain their process: Don’t overcook the cabbage, to maintain texture; add the garlic and spices at the end, to enhance flavor; and don’t forget the Maggi seasoning. Although happy to explain their recipe, they seem perplexed by the interest. Eyebrows are raised and a slight smile responds to every cooking question. To the women, this stew is normal, as exotic as a cheese pizza to the average American. Ariane explains that this stew is eaten both for celebrations and for family meals. Back home in Cameroon she was a chef, but she isn’t particularly proud of the title, instead emphasizing her profession as a hair dresser. “All women in Cameroon are expected to know how to cook,” she says. “That’s one of the main skills a woman must have before being married.”

To accompany the stew the women also make fufu, a starchy staple consisting of corn or cassava flour pounded and formed into a dense ball. Since cassava is difficult to obtain in Greece, the women decide to make the corn version. They take turns stirring the corn flour, taking several breaks during process. Ariane take the opportunity to video chat with her children in Cameroon. Despite their friendly demeanor, the women remain guarded about their personal lives outside of Greece. West African refugees come to Europe seeking economic opportunities, fleeing political instability or regional conflict. Almost all arrive with the help of smugglers and many refugees are not eager to disclose their experiences, for fear of drawing unwanted attention from the Greek authorities.

As evening approaches, the refugee guests start to arrive—mostly African men from Cameroon and other West African countries. The men are in their 20s to early 30s and sit quietly, transfixed by their phones—a trait that seems to afflict young people everywhere. However, anticipation builds as food begins to arrive at the table. Most refugees live in large government-run camps, with tasteless government-issued meals. This food will be the first time many of these men have tasted their native cuisine in months.

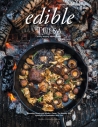

The fufu is brought out first, wrapped in aluminum foil to maintain its heat. The stew arrives next, separated into a pork and beef version (beef for the Muslim guests, for whom pork is forbidden). Forks and spoons are passed around but the traditional way to eat is with your fingers, which some of the men demonstrate for the non-African guests. Taking a bite-size piece of fufu, the men press a small dent into the center and use it to dip and scoop up bits of sauce and food. The stew has a smooth texture, with a subtle crunch from the cabbage, and despite being cooked with copious amounts of peanut butter it doesn’t overwhelm with the taste of peanuts.

A few Pakistani refugee workers at the restaurant also join the meal. Conversation at the table descends into a dizzying array of English, French, Greek and Urdu, all being spoken simultaneously. Regular dinner service has begun and the restaurant is soon teeming with tourists from America or Europe. Many of them look over at this peculiarly international table with curiosity. Is this a celebration? What kind of food is that? How do I order that from the menu? For a few hours, these refugees can be the subjects of people’s envy instead of pity. And that is a welcome change.