Nomadic Himalayan Fare, at Home in Woodside

Five years ago, Ngodup Gyaltsen was crammed into a packed subway car with a cart of warm, homemade spiced beef and chicken dumplings, counting stops to find his way to his destination. Gyalsten spoke Tibetan, Nepali, Hindi and a bit of Mandarin, but could not speak or read English, so he negotiated the expansive New York City subway system by memory, every morning hoping to not be thrown off by a rerouting or a skipped stop.

Gyaltsen, originally from Tibet, began cooking momos at his home in Woodside in July 2013, and carted them through the city. He first sold them at the city’s largest farmers market—Union Square Greenmarket—then at its second-largest at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn. Many Tibetan New Yorkers work at farmers markets and art and holiday markets around the city. He soon fanned out to the smaller markets and art fairs, and to hotels where Tibetan New Yorkers work as housekeepers and doormen—anywhere Tibetan people were in need of hot, fresh lunches that reminded them of home.

Years later, Gyaltsen would help open a restaurant that would be written up in the New York Times, serving the nomadic Tibetan food he grew up with, in elegant ceramic bowls. Lugging his trolley up steep subway stairs into the din of the city, he forged a story that is as unlikely as his community’s.

The Tibetan diaspora in New York City is often neglected in national and city statistics because Tibet is not internationally recognized as its own sovereign nation; many Tibetans have come to the city by way of other countries. Tibetans are culturally distinct by language, religion and ethnicity from immigrants from India or Nepal, with whom they may share a migration route, as well as those from China, with whom they share a nation.

The stream of refugees leaving their homeland is a direct response to the degradation of culture and livelihood on the Tibetan Plateau. More and more of those refugees are settling in New York City. In 1992, the New York Times stated that there were all of 125 Tibetans in New York City. The 2010 census counted 3,527 Tibetan speakers in the state of New York. By 2015, the census estimated that 7,800 Tibetan speakers were living in New York State, 5,705 of them—73%—in Queens.

Even those figures are assumed to be a vast underestimate. The Himalayan community here is large and heterogenous, speaking a wide variety of Tibetic languages that share origin and script with Tibetan. It is estimated that there are over 20,000 Himalayan people in New York City.

Today, Gyaltsen and his daughter, Dawa Bhuti, run a renowned Tibetan restaurant in Woodside. While Gyaltsen is from Tibet, Bhuti was born in Nepal during their family’s migration, and learned to cook in their adopted home of New York City.

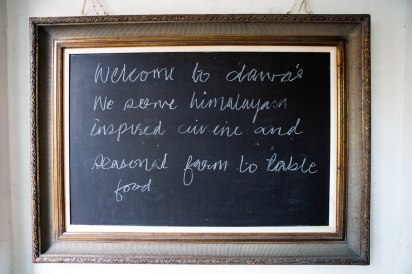

Dawa’s is a restaurant rooted in its cross-cultural identity, arising from a culture and a community displaced. Gyaltsen cooks traditional Tibetan food, whereas Bhuti’s cooking has an American touch from many years of cooking in New York City restaurants, and is influenced by her apprenticeships in India and Italy. They each claim a side of the sparse, elegant menu. On the American side, you can choose from options like citrus and avocado salad, steamed wild cod or butternut squash risotto. Tibetan options include gyuma (Tibetan blood sausage), thenthuk (pulled noodles in bone marrow beef broth with sliced beef and daikon disc) and tsel-baley (vegetable patties filled with garlic chives and yu-choy greens). Diners can mix and match dishes as they please from both sides of the menu.

As his business selling momos to Tibetan market workers grew, Gyaltsen added a daily special such as rice and dal with vegetables and chicken or roti with potatoes. He would also pack large thermoses of butter tea to distribute with his lunches. Six days a week, Gyaltsen would produce 30 lunches and almost as many dinners in his family’s kitchen, starting at 5am. His daughter watched him toil while working on a livelihood of her own in Queens.

Bhuti told me her story and translated her father’s from the back table in the restaurant they co-own. When seated, Bhuti massaged her hands, seeming anxious to rise and accomplish things. Her strong forearms marked her as a chef and her face reflected her father’s, but her manner was more assertive and open.

Bhuti was born in Nepal, after their family left Tibet in the wake of political turmoil. She went on to attend boarding school in India, culinary school in New York City and apprenticed in kitchens across Europe. When her father was delivering lunches to markets across the city, Bhuti was finishing culinary school and toggling two kitchen jobs as well as work as a personal chef. One Saturday, she had a day off from all of her jobs, and offered to help her father.

They cooked together and headed out for the day. She watched him negotiate for space on the crowded subway, getting pushed and insulted on the train. She helped him carry heavy loads of food up and down stairs. She didn’t feel ready, but she decided it was time to open their own place together—she hated watching her father struggle. It took Bhuti six months to transform a small bakery and deli into their open, light-filled Tibetan restaurant.

The butter tea at Dawa’s—served in a thick, handmade mug—is unashamedly salty and rich. The restaurant itself is airy and bright, with plaster walls painted white and simple wood tables, each slightly different. Fresh-cut flowers in glass jars or handmade pottery sit on every table. Food and drink are served in ceramic mugs and bowls in neutral colors, earthen but perfectly thrown—symmetrical, strong and smooth. The restaurant feels like an expression of Bhuti herself: thoughtful but uninhibited; focused on the essence of things.

On a Saturday in early May, Bhuti took me out back to see her garden. It had been a long, cold winter and the ground was still a bit barren. Garlic greens stood tall from a planting in late fall. Potatoes were planted more recently. A trellis she’d made from thin plastic pipes and wooden stakes would soon support the vines of bean plants. Basil, oregano, thyme and rosemary grew nearest the kitchen door, where Bhuti can find herbs quickly in the middle of service. At the back of the small yard she’d planted buckwheat, the leaves of which she’d mix with yogurt, chili and garlic, in a traditional Tibetan dish eaten cold with rice.

She said she treasures the things that grow wild in Tibet but are so hard to find, or expensive here. She loves nettles and ramps. She tells me about how rhubarb is used for dyeing clothes in Tibet and how it is eaten raw, as a snack, by people grazing cattle in the mountains.

Bhuti was born in Nepal, not Tibet, but she learned about these wild foods at an early age, and they remain essential to her. As the eldest daughter, her parents taught her to cook traditional Tibetan cuisine. The blood sausage she serves tastes just like the blood sausage that you would eat in Tibet, she says, adding, “It gives you a feeling that you’re still at home.” When I ask where she means when she says home, she says that she’s not quite sure. “My blood is Tibetan.” She opens a metal hatch leading down to the basement to show me her bean seedlings, protected from the birds and just beginning to sprout.