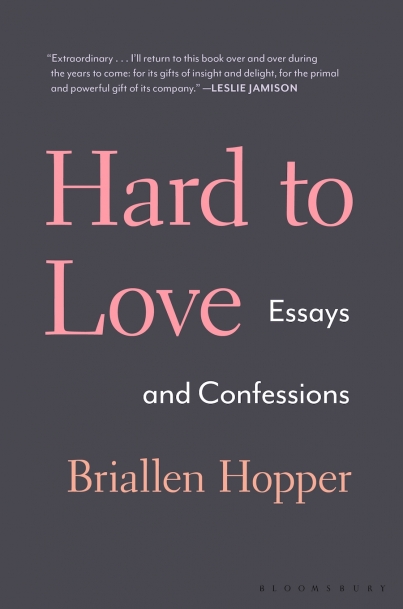

Hard to Love: Essays and Confessions

Baking as a woman can be fraught. It’s often seen as soft and feminine to pipette a layer cake or trim and crimp a piecrust (picture Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, who hums a sweet song while little forest creatures help her tame the dough). The Suzy Homemaker image of a 1950s housewife retrieving a piping hot baked good from the oven is well ingrained in our collective consciousness, and it can be hard to break free from its strictures (And yet, in professional kitchens, men dominate).

In an essay titled “Tending My Oven,” from Briallen Hopper’s book Hard to Love, the author—currently a Queens College assistant professor of creative nonfiction—opens with the poem “Black Coffee” by Paul Francis Webster, for which her essay is named.

“Now a man is born to go a-lovin’

A woman’s born to weep and fret

To stay at home and tend her oven

And drown her past regrets

In coffee and cigarettes… ”

Hopper writes of one friend who, when she started teaching at Yale, was advised by an older female mentor not to “tend her oven” for her students, lest they not take her seriously. But she rebelled against that, and leaned into from-the-heart baking wholeheartedly—“For Cathy, unapologetically bringing her students cookies is a way of resisting the system that says that brains matter and bodies don’t; that men matter and women don’t. It’s a symbol of what she isn’t willing to let go of in order to be taken seriously,” Hopper writes.

Formerly a Yale writing professor herself, Hopper talks of her own love of baking, especially for her students. She first learned how to bake from her mother, but became passionate about late night bake-a-thons and compulsively crafting cakes from scratch in her 20s. For Hopper, baking became her language of love, “a code for conveying care safely without the dangerous ambiguity of words.”

She reflects on the concept of “tending one’s oven beyond domestic drudgery,” and explores the gendered dynamics of whipping cream and stirring out clumps—“Is tending your oven a way to fight the patriarchy, in other words, or is it a capitulation to it?” To do so, Hopper interviewed other women who enjoy baking for others, some who are conflicted about what that says about them as feminists, others who are unabashed. One friend tells Hopper that baking, for her, is about “feeling good, wafting along in the warm, sweet-smelling air, unwinding, no longer being entirely an office creature.” Another says it simply allows her to be her “softest, most vulnerable self” away from the energy and fight that goes into her daily life outside of the kitchen.

“Tending My Oven” is just one essay in a 324-page collection that examines other variations of the same conundrum—choosing softness in a society that says to do so is weak, creating your family and community on your own terms, when you’ve been raised to view the nuclear structure as the ideal. It seems clear that Hopper is firmly on Team “Who Cares If the Patriarchy Says Baking Cupcakes Is Foolish?” and a proponent of finding and celebrating relationships and love found outside of marriage.

Even her book’s subtitle “Essays and Confessions” is a subversion: In an interview on the literary website The Rumpus, Hopper said, “The confessions part [of the subtitle] has both a serious religious resonance, where it’s like I’m confessing my deepest experiences and beliefs here, and this salacious quality, too, where I’m going to let it all out. That’s associated with trashy pulp magazines and women writing on the Internet. All of those different resonances of the word confessions came into play. I wanted to write a book about my deepest beliefs and spiritual experiences and also one where I shared shameful stuff.”

Baking is labor intensive; it’s hot, physically demanding, and requires endurance, precision and not a small amount of arm strength. It’s also a mode of communication. Sometimes pear tarts or mixed berry galettes can express something from the heart more easily than words. As Hopper said in that same Rumpus interview, “One of the reasons why I bake is that it is a very straightforward way of connecting with people. You could be having all sorts of problems in your friendship, but you can still make and share baked goods, and you can still express and receive love in that way.” She continued, “That is in my wheelhouse. I think baking is a good go-to if you need some mode of communication that’s not words, and I think it’s been that for me in a lot of different contexts.”

Hard to Love. By Briallen Hopper (Bloomsbury, 2019)

—

RECIPES:

March of Resilience Cupcakes

This simple vegan chocolate cake supposedly dates back to World War II and the days of rationing. In her 1960 culinary classic The I Hate to Cook Book, Peg Bracken calls her version “Cockeyed Cake.” It is also known as Wacky Cake and Crazy Cake. I got the recipe from Cathy years ago, and by leaving out some or all of the cocoa and adding other flavors I have turned it into mocha cake, red velvet cake, funfetti cake and pink lemonade cake. It is fast and almost effortless, and you can make it even when you’ve run out of eggs.

In a big bowl, mix:

3 cups flour

2 cups sugar

1 cup cocoa (feel free to substitute other flavorings)

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

In a smaller bowl, mix:

2 cups water (or leftover coffee for a more complicated flavor)

⅔ cup oil

2 tablespoons vinegar

2 teaspoons vanilla

Pour the wet ingredients into the dry and stir it all together. The batter tastes like chocolate pudding, and since there are no raw eggs it’s safe to lick the spoon. There is enough for 2 dozen cupcakes or 2 layers of a layer cake. Bake at 350°, about 15–25 minutes for cupcakes and longer for cake. You’ll know it’s done when you stick a fork in it and it comes out clean.

For the frosting:

1 stick butter

8 ounces cream cheese (i.e., 1 whole silver-foil rectangle of Philly)

1 teaspoon vanilla

Peanut butter to taste (optional)

3 cups powdered sugar

Beat the butter and cream cheese together for several minutes till creamy (a hot red KitchenAid is quite useful for this). Add the vanilla and peanut butter. Then sift in the powdered sugar a bit at a time. Wait for the cupcakes to cool before frosting them.

Love Is Hard but Shortcake Is Easy

There is a hard way to make shortcake that involves painstakingly cutting small pea-sized pieces of chilled butter into triple-sifted flour, rolling out the dough until it is perfectly smooth and even and cutting out each piece of shortcake with a biscuit cutter or an upside down glass tumbler. This is not that way. This is the easy way.

Begin by washing the fruit you’re using, slicing it if necessary, sprinkling it with brown sugar to coax out the juices, and putting it in the fridge in a covered bowl.

My favorite flavor combinations are strawberry and blackberry or peach and blueberry. You will also need cream. Whipped cream in a can is a magical food. If you make homemade whipped cream, drizzle a little molasses into it.

In a big bowl, mix:

4 cups flour

4 teaspoons baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

½ cup sugar (leave out the sugar if you want delicious drop biscuits)

1½ teaspoons salt

Between 3 and 4 cups heavy cream (enough that the dough is malleable but not impossibly sticky)

It’s thick dough, so you will end up mixing it with your hands. Form it into 16 shortcake-shaped lumps and drop them on baking sheets and bake at 400°F till done to taste. (I start checking on them after about 10 minutes.) Some of my friends like their shortcake medium-well and toasted on top; others like it rare and ender. I like to make 1 sheet of each.