Lessons Learned

In the interest of full disclosure, school Principal Robert Groff would like you to know: He’s not vegetarian. And when he founded P.S. 244 in a predominantly Chinese-American enclave of Flushing, in 2008, he didn’t envision creating a vegetarian school, either.

But he did establish P.S. 244 with an emphasis on health and nutrition, which is how, in 2012, it became the first public school in New York City to go vegetarian. Students participated in monthly tastings and supplementary physical education classes. So when, two years into the experiment, a third-grader approached him and asked why their cafeteria had chocolate milk, considering its high sugar content, Groff took the opportunity to reevaluate the school’s menu—and how it reflected the wellness principles it espoused.

“That was the spark,” Groff said on a humid June afternoon last year, just before the end of the school year. “We started going down uncharted territory.”

At the time, there wasn’t even a vegetarian menu for the school to adopt; all public schools cooked up the same Department of Education–mandated lunches, which meant a lot of burgers, chicken nuggets and foods that were only incidentally vegetarian, like mozzarella sticks. So Groff worked with the DOE’s Office of Food and Nutrition Services and the Coalition for Healthy School Food to develop and test vegetarian options, seeing what the kids liked (pizza is always a hit) and disliked (tofu has proved a struggle, especially considering it has to be served in a DOE-approved two-ounce block).

The nascent program aligned nicely with the Obama Administration’s new nutrition guidelines—rules implemented as part of 2010’s Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act required menus to include twice as many fruits and vegetables and only whole grains. It represented the first update to the federal school lunch program in 15 years—and it fell in the midst of PS 244’s efforts to go fully vegetarian.

Since then, the nutritional value of school lunches nationwide has increased—by 41% from the 2009–10 to 2014–15 school years, according to a study released by the United States Department of Agriculture in 2019. At P.S. 244, Groff said he’s seen a transformation: Teachers say their classes have more energy after lunch; attendance has increased from 95% to 97%; and test scores have gone up, though he conceded it’s impossible to attribute these solely to the vegetarian menu without data. According to OFNS supervisor Sylvia Banton, the proportion of students who eat school lunches has remained steady: during the 2014 to 2015 school year, the oldest data she provided, participation ranged from 390 to 405 of an enrolled 440 students; so far during the 2019 to 2020 school year, participation has ranged from 415 to 445 of an enrolled 474 students.

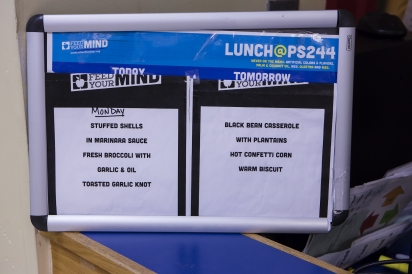

When I visited the school during a dismal rain last summer, recess was held inside and a lot of restless bodies crowded into the cafeteria. Second-graders squirmed on picnic benches, tucking into the daily offering of peanut butter and jelly or cheese sandwiches—on whole-grain bread—or the day’s special: veggie tacos in hard-shell tortillas with a smattering of sweet plantains on the side. Every month, the DOE releases a menu and recipes to school chefs; individual schools don’t have much agency over what’s served, but administrators like Groff are lobbying for more vegetarian options—a veggie burger, perhaps, or not-dog.

Pizza remains a favorite—one day last school year, all but eight of 445 elementary schoolers ate the cafeteria’s pizza lunch, Banton said—but Hally, a second-grader, told me she tries something new every day; Roha, another second-grader, discovered she loves dried kiwis and requests vegetables when her mom goes grocery shopping. They caucused briefly about the “orange thing”—cantaloupe, I gathered—before deciding they were in favor.

“Parents come in and shake their heads at me and say, ‘I’m not allowed to eat this now’—in jest,” said Greta Hawkins, the principal of Coney Island’s P.S. 90, which went vegetarian three years ago to complement its environmental studies–focused curriculum. Participation in their program hovers between 50 and 75%, depending on the day’s menu.

Two other schools have gone vegetarian since 2012: Manhattan’s P.S. 343 did so in 2013, after Principal Maggie Siena heard a story about Groff’s school on NPR; and Sunset Park’s P.S. 1 in 2017. After a successful pilot program among 15 schools in Brooklyn, public schools citywide began participating in “meatless Mondays” during the 2019–20 school year. (According to Groff, who coached the other schools’ administrators through the transition, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams has been a particular proponent of vegetarian lunch options.) And last fall, the New York City Council passed a resolution recommending a ban of processed meats in school lunches. “We need to grow as a network,” Groff said. “We’re not the only ones doing strong health and nutrition work.”

On a local level, the project Groff initiated nearly a decade ago has made major strides. But federally, the Trump Administration’s Secretary of Agriculture has vowed to undo those Obama-era health regulations. In 2018, the USDA announced that it would reduce whole-grain requirements by half and reintroduce low-fat flavored milks, citing schools’ alleged difficulty in meeting the guidelines set in 2010. (In 2016, the USDA reported that more than 99% of schools nationwide did manage to meet the guidelines.)

The new USDA rules went into effect in the first half of last year; meanwhile, New York and a group of five other states, as well as Washington D.C., sued the Trump Administration for what state Attorney General Letitia James described as “attacking the health and the safety of our children.” When we spoke last summer, school administrators were still figuring out how the new regulations might affect them: “We don’t quite like the idea,” Hawkins said, “and we don’t know what it’s going to mean for our students.” Siena added separately that she hoped the city’s Department of Education would “be a firewall.” Still, the rollback seems unlikely to pose much of a threat to New York City’s public schools, including the vegetarian schools. Banton noted that nutrition standards have only improved, and breads, pastas and other grains are all whole grain; according to the Department of Education website, the city has continued to “meet and many times exceed” the USDA’s rules. Amie Hamlin, the executive director of the Coalition for Healthy School Food, said she’s confident the city will “keep doing what they were already doing, because they know that’s what’s best for kids.”