Queens Bakers Rise to Resist

I can still recall one of the first times I strayed beyond PS1 and 5Pointz (RIP) to explore Long Island City, and was led by the nose, Looney Tunes style, to a nondescript block in a commercial part of the neighborhood. A beige brick building emanated the sweet scent of fresh-baked bread: the aroma of home, heady in the summer heat.

It seemed whoever was baking in there was no less than a wheat wizard. It was the Tom Cat Bakery, a commercial bakery operating in the neighborhood since 1987. Then, as today, the bakery provided specialty breads to hundreds of restaurants, cafés and retailers throughout the Greater New York area. Its silver trucks and feline logo are a common sight for commuters in every corner of the city, day or night.

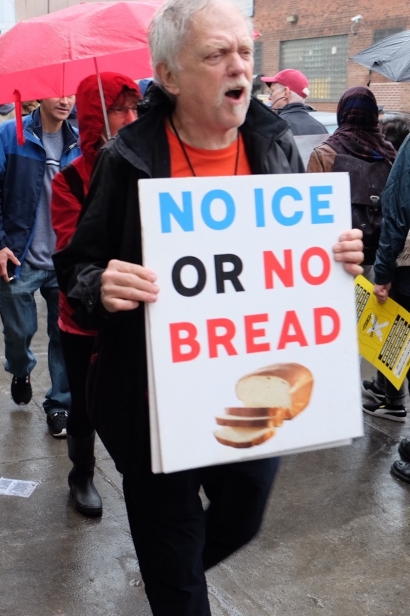

My memory of that fond first encounter made it difficult when I learned that Tom Cat was the subject of an I-9 audit from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a branch of the federal Department of Homeland Security (DHS). More disappointing yet, it seemed the business intended to categorically dispatch workers who had given them decades of work to avoid fines of up to $21,916 per worker. Tom Cat Bakery declined to comment for this story.

Imagine working at a job for two dozen years, perfecting your craft and doubling your output (thousands of kilograms of bread per day), and then being told you will be fired in 12 days—without severance. This is the reality that 31 Tom Cat Bakery workers faced when they received a letter from management on March 16.

“After an ongoing audit, it was brought to our attention that documents you provided at the time of hiring in form I-9 does (sic) not currently authorize you to work in the United States,” read the letter.

Workers reacted with alarm, despondence and disbelief. “I felt sad, I never expected this would happen,” said 12-year Tom Cat employee Oscar Ramirez upon hearing the news, “I worked there a long time and I feel betrayed.”

But that same night he and the other workers got to talking and resolved to fight back. The prospect of media spotlight through protest was a daunting one, especially for Ramirez, who feared he might be separated from his special-needs child. Luckily, the workers would not stand alone in mounting a response to the immigration inquiry. An unprecedented wave of activism has swept the nation since November’s divisive presidential election, empowering groups already working for change and inspiring new ones to form. In these activists, the Tom Cat workers found their allies. This case may be a first indicator of how the Trump administration will pursue what many see as xenophobic policies in the years to come.

When I first arrive to the single-room Brandworkers office, roughly a dozen heads jolt upward and a handful of discussions in English and Spanish trail off just for a moment before picking back up. The organization is a nonprofit that backs worker-led campaigns for more sustainable labor practices within the food industry.

Daniel Gross, Brandworkers’ executive director, jumps up to greet me but is waylaid by staff seeking his input. Over the course of the hour, Brandworkers employees, activists, board members and Tom Cat workers (not mutually exclusive groups) pass memos to Gross and ask for his feedback every five minutes. Despite the rapid pace of work, the mood in the space is not frenetic, and Gross has the serene disposition of a Zen master.

“This is a space where workers come together and determine their own way forward,” says Gross. He started Brandworkers in 2007 as he was graduating Fordham Law after a colleague asked him to meet with seafood processors with concerns about their workspace. “There’s a really significant sector of New York City’s food system that’s out of sight, out of mind, where food is manufactured,” says Gross.

Tom Cat workers approached Gross on the night of March 16 with the letter. Brandworkers immediately initiated their rapid-response protocols. For Gross, who says he hasn’t been aware of such an inquiry in the New York area since a case involving FreshDirect 10 years ago, the turn of events did not elicit surprise. At an activist awards dinner this past November, Gross expressed concerns that the Trump administration would target members of the New York manufacturing community. “Although,” he says, “I didn’t expect us to be the first.”

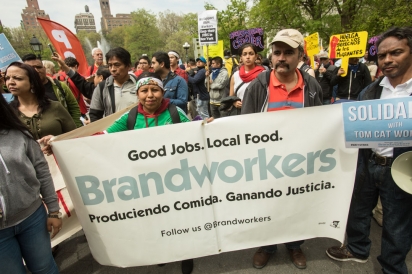

The Brandworkers team and the workers organized a rally on March 21 outside the Tom Cat building, attracting interest from the press and local politicians. A GoFundMe campaign was created to raise emergency funds for rent for each of the at-risk workers. At press time, the page had raised just under $30,000 of its $77,500 goal. Facing termination and fully understanding the extent of punishments they risked from ICE, the workers chose to raise a banner for what they saw as injustice, rather than hide.

“The workers had a really important choice, and this is a choice facing workers in New York City’s food system and those all over the country, which is: ‘Am I going to run?’” says Gross. “And they chose to stand united and fight—it’s amazing to see the human spirit here.”

After the initial rally, DHS extended the deadline for workers to turn in documentation until April 21. On the day Tom Cat initially planned to fire workers unable to comply, they changed course and publicly offered to assist staff members in any way they could to produce the necessary documentation, though Brandworkers representatives claim Tom Cat’s actions remained hidden.

Workers, organizers and their legal team got to work planning next steps. They rallied outside Trump Tower on April 8. Afterwards, as the new deadline approached and the company remained a stone wall, it became clear that the workers would lose their jobs, so they organized a campaign called the “Day Without Bread” for April 21.

A company spokesman told The New York Times that the Tom Cat inquiry began in December, at the end of Obama’s presidency, but the investigation is being presided over by the Trump administration, and is in lockstep with the anti-immigrant rhetoric the president used during his campaign.

Gross suggests that ICE may have been emboldened by the election results. In numbers recently reported by the Washington Post, overall arrests made by ICE from January 20 to March 13 increased from 16,104 in 2016 to 21,362 in 2017 over the same period. Within those arrests, the percentage of non-criminal arrests has more than doubled, and it remains to be seen whether this is part of a rising trend. These are fewer arrests than under the Obama administration in 2014, which is indicative of a more entrenched US immigration policy, as some activists are quick to point out.

“The systems that this administration is using [to pursue immigrants] have been a part of every administration,” says Ora Wise, culinary director of Harvest & Revel. The Brooklyn-based catering company is a champion of ethical practices in all aspects of the kitchen, whether in sourcing its ingredients or providing for their workers. Wise believes long-standing US economic and trade policies foster a dependency on an underpaid workforce to come into the country by any means, only to be criminalized by the justice system.

Harvest & Revel supported Brandworkers for the “Day Without Bread” and donated a portion of the bread sales it made that day to the workers’ cause. Wise was joined in this action by chef Max Sussman of Samesa. Both chefs are part of the Food Issues Group (FIG), an informal collective of chefs, managers, growers and distributors who explore sustainability issues and put them into practice in their businesses. Wise believes the ideas the group has explored have helped to improve her own business for her employees. “When we carve out a space to educate ourselves about the issues and spend some time thinking about them together, then we’re able to come up with more creative strategies for change,” says Wise.

The sustainable labor practices Wise espouses are ones that Gross would consider “Brandworkers standard,” part of what he sees as a healthy 21st century food system.

April 8 was a blustery day, but amid all the wind I could hear chants coming from the southwest corner of 57th Street and 5th Avenue. There, a barricaded crowd of about 80 shouted, “Si se puede!” and “No borders, no walls; Immigrants, they feed us all!”

“When restaurant workers are under attack, what do we do? Stand up, fight back!”

Central to the group are the workers themselves, who Gross says come up with all the ideas for their actions. Supporters like human rights activist Michele Burger came to join the group; she said her parents came to this country “to espouse liberty and freedom for all.”

Hector Solis, a 12-year Tom Cat employee native to Mexico City, spoke of his wife and two children, and said that he just wished to continue working to support his family. “I feel so sad and so angry at the same time, because it’s not really fair what they’re doing to us. We’re not criminals like they say we are. We’re good people, good workers. We work hard to do the best we can.”

I next saw Solis, all smiles, at the “Day Without Bread” rally outside the Tom Cat bakery at dawn on the cold and rainy morning of April 21—the day that any workers unable to provide documentation were to be terminated. The group had won the support of many allies: New York Immigration Coalition, RWDSU, Restaurant Opportunities Center United, Food Chain Workers Alliance, Make the Road, New York Fight for $15 and ACLU People Power all circulated a petition that day.

The organizers of the Yemeni Bodega strike in February, a response to the so-called “Muslim Ban,” declared solidarity with the Tom Cat bakers. Some bodegas promised to go along with the day’s plan to shut down all sales of bread in the city. In the morning’s dim hours, four Brandworkers supporters (none of them Tom Cat employees) were arrested for chaining themselves under Tom Cat delivery trucks in an effort to slow down the company’s production. Ramirez, a leader among the workers, was fired two days prior, and while matters were unclear during the morning hours of the protest, as of press time, 26 of the initial 31 targeted employees have been let go.

And yet, none of the workers seems to have given up the spirit of the fight. Amidst the cool morning light, the workers came forward one by one to say who they were and to implore the crowd to join them in taking part in the May 1 general strike. Afterwards, they marched up and down the block to the brassy tones of the Rude Mechanical Orchestra, an impromptu protest marching band. Reflecting on the past month, Gabriel Morales, Brandworkers’ campaign director, said, “It’s been amazing, really. Every day I’m just floored by the boldness of thought and willingness to take hard action to combat what is really just a busted system.”

Brandworkers | @brandworkers

Daniel Gross | @dorganize

FreshDirect | @freshdirect

Harvest & Revel | @harvestandrevel

Max Sussman

Samesa | @samesarestaurant