Politics and Pupusas: Shifting government policy takes toll on local Salvadoran restaurants

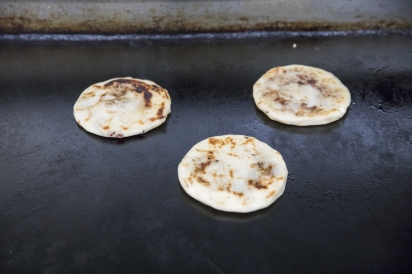

Over the past decade, the pupusa—a traditional Salvadoran food staple—has found increasing popularity among food lovers in New York City. Take a trip to any food market or flea and chances are you will hear the familiar hand slapping that comes with the making of a fresh pupusa.

But before they were so sought after, pupusas and the restaurants that served them were vital to the small Salvadoran community new to New York City.

In the early ’70s, pupuserias were hard to come by. The few Salvadorans in New York City had to make treks out to Jersey City, Connecticut or even Boston to get authentic food and ingredients.

By the late ’80s, the Salvadoran population saw a sixfold increase. El Salvador’s civil war and instability throughout Central and South America forced many to migrate to the United States. The majority gravitated to the West Coast but many made their way to New York City, specifically to Queens and Long Island.

As is the case with many immigrant communities, many arriving Salvadorans found work in kitchens and restaurants throughout New York City.

In the aughts, after just getting out of a two-decade-long civil war, El Salvador was struck by a series of devastating hurricanes and earthquakes, prompting another large migration. Due to these natural disasters and further instability in El Salvador, roughly 200,000 Salvadoran immigrants arriving to the United States were granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS). TPS is a legal status intended to protect immigrants from being sent back to a country that would put their lives at risk. In New York City, approximately one in every eight Salvadoran immigrants is a TPS holder.

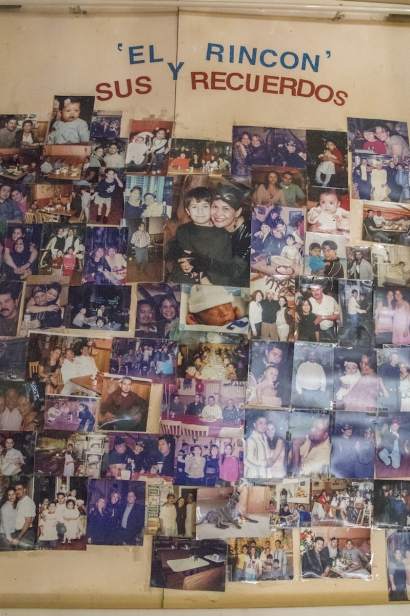

With this Salvadoran population boom, restaurant owners saw their businesses grow and flourish. More restaurants and markets stocking Salvadoran foods opened to fulfill the growing demands of the community. Restaurants began serving not only the children of their early patrons but grandchildren as well. As the population began spreading to other states such as Virginia, Georgia and Washington, DC, those who remained continued frequenting their favorite restaurants-cum-community hubs.

Birthdays, anniversaries and other occasions, happy and sad, were marked by gathering the family and heading to a Salvadoran restaurant. Their businesses were no longer just places to purchase food but gathering places to feel connected to home. For many just arriving, they were also sources of information, places they could find jobs and where they’d go to keep up with news from home.

Early this year it was announced that TPS would be terminated in 2019 for immigrants from Sudan, Nicaragua, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Syria, Yemen, Somalia and El Salvador. It is estimated there are 4,200 Salvadorans in New York City with TPS. Of course, this news has been met with fear over the uncertainty of their futures. Most of the restaurants we spoke to have stated that since the announcement business has declined by about 20%. Some believe that their patrons are saving their money in case they are forced to leave next year. They lamented that the same dream they came here to pursue and achieve does not seem attainable for the next generation of immigrants.

These restaurant owners show how immigrants contribute and help foster growth in the community. These successful businesses allowed them to create better lives for themselves and their families, who are still involved in the family business. Some have become entrepreneurs themselves. Elena, the owner of Rincón Salvadoreño, has sons who opened their own business in Jamaica, called Café Energy. Astrid Portillo, the owner of Salvatoria, is the daughter of Margarita, who opened Mi Pequeño El Salvador.

Rincón Salvadoreño

Café Energy

Salvatoria | @salvatoriakitchenbar

Mi Pequeño El Salvador