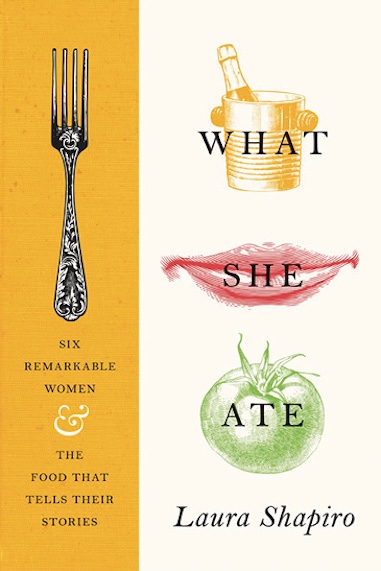

What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories

Nothing tells the story of a person like what they eat or don’t eat, how much of it they eat, how spicy it is, or whether it’s a mostly liquid diet. It’s biographic data that, as Laura Shapiro points out in the opening pages of What She Ate, isn’t often included because “biography, as it’s traditionally practiced, tends to honor the old-fashioned custom of keeping a polite distance from food.”

Shapiro’s research is meticulous and acute, and her anecdotes are woven together for maximum effect. No matter how much you know about Eleanor Roosevelt, it’s hard to get a sense of who she was—not as a historical figure but as a real, complicated, day-to-day woman.

Yet Shapiro approaches her subjects—six women from different eras and backgrounds, from Helen Gurley Brown to Hitler’s mistress—like a compassionate detective, using diaries, grocery lists and interviews—the latter used well in the case of Rosa Lewis, the high-climbing, eccentric Edwardian-era caterer and fur-clad hotel proprietor.

Shapiro culls from a 1925 biography by journalist Mary Lawton, the result of interviews with Lewis in London. The royal chef became enchanted by aristocracy while working at the home of an exiled French count around 1886. She gained access to that world through the kitchen. “I learnt to think...” Lewis told Lawton, “it was not a stupid thing to cook. I saw that the aristocracy took an interest in it, and that you came under the notice of someone that really mattered.”

Dorothy Wordsworth is the historical figure rendered most uncrackable. She had an intoxicating, close relationship with her poet brother; Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journals piece together an idyllic time for the siblings, living together in the lake district. She enjoyed taking care of William, whom she idolized. Whether it was finding the “thick” gingerbread he preferred or making “savory pie filled with veal, rabbit, mutton, giblets or leftovers,” the meals were dutifully recorded in her journal—a reminder that sacredness resided not just in her brother’s picturesque lakeside rambles but also in daily sustenance.

English novelist and marvelous spinster Barbara Pym is my favorite portrait; I relate to her compulsive need to record the world around her. Food, and paying attention to it, was a recurring theme in her books. In her daily life, she kept the sort of scattered remembrances and phrases writers are wont to keep track of.

She was a fastidious chronicler of people’s eating habits as a way of figuring out what that person was about. Both Pym and Shapiro share the characteristic of documenting the world with warm and optimistic insight into the lives of others.

“This middle-aged lady is sitting in Lyons reading the Church Times and eating Scrambled Egg Beano.” wrote Pym.

In an interview with Eater, Shapiro shared her signature meal: Quiche made with sliced fried onions, mild cheddar cheese and a butter cracker-crumb crust, which she insisted should be made of Ritz crackers.

In the same interview, Shapiro reveals that Eleanor Roosevelt is her favorite portrait. Roosevelt, out of perhaps all the unique women featured, had the most complicated relationship with what it meant to be a woman in the kitchen. She had to reconcile her deep aversion to being a First Lady existing solely for “drawing room duties,” as an Associated Press 1932 headline wrote.

The cook she hired as White House chef was stunningly inexperienced and served “sick-looking” meals. It’s been speculated that the pallid meals were, in part, retribution for her husband’s infidelity, but more likely, they spoke to Roosevelt’s feelings that meals were best served with maximum efficiency. Shrimp Wiggle is one of the dishes the White House served from one of its leftover-based lunches—shrimp and canned peas in white sauce on toast.

Eva Braun, Hitler’s consort whom he later married, is the least sympathetic figure by far, but Shapiro skillfully humanizes the naive and monstrous dame, whose warped, childlike femininity encased her obsession with her husband. Consumed by dieting and Champagne, Braun literally let the world burn around her while eating cake. The details of her and Hitler’s dinners illustrate actual humans instead of otherwise broad, shapeless strokes of monstrosity.

“What emerges most vividly in Eva’s relationship to food,” writes Shapiro, “is her powerful commitment to fantasy. She was swathed in it, eating and drinking at Hitler’s table in a perpetual enactment of her own daydreams.”

Last but not least, Helen Gurley Brown. Despite her ultra-feminine, sex-friendly career gal persona, Brown was husband-obsessed. Her contradictory attitude towards food mirrored her attitude towards men and marriage—she had an almost kinky desire to be a submissive housewife, insisting her husband give her an “allowance,” even when she brought home a considerable amount of their income from Sex and the Single Girl’s success. She dieted to the point of anorexia, but most mornings cooked her husband Welsh rarebit, eggs Benedict, roast beef hash and codfish cakes from scratch.

Shapiro writes, “We’re meant to read the lives of important people as if they never bothered with breakfast, lunch or dinner, or took a coffee break, or stopped for a hot dog on the street or wandered downstairs for a few spoonfuls of chocolate pudding in the middle of the night.”

Now, thanks to 10 years of research, paying attention and understanding that phrases and meal plans scrawled as afterthoughts can say so much, Shapiro tells us, for six women, what those spoonfuls of chocolate pudding in the middle of the night tasted like.