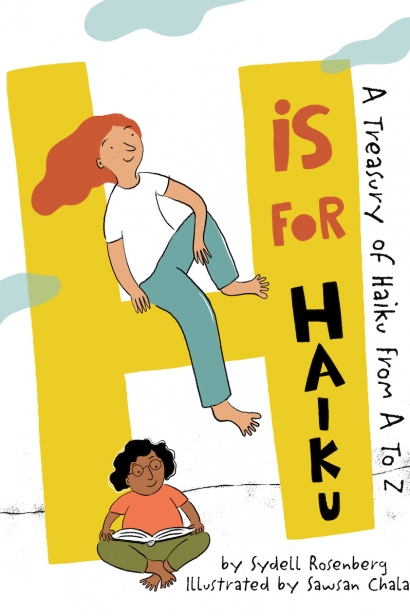

H is for Haiku: A Treasury of Haiku from A to Z

As cliché as it is that a great piece of writing can transport you, it’s true. The haikus in H is for Haiku, written by the late poet and Queens educator Sydell Rosenberg, paired with vivid city scenes illustrated by Sawsan Chalabi, are capable of whisking away even the most poetry-averse—down snow-covered streets, headlights beaming down country roads, jockeying along with galloping horses, plunging downhill with a girl on a bike, petals falling in her hair.

H is for Haiku is a posthumously published romp through the alphabet—inspired by Rosenberg’s experiences living in New York City—intended for children, but every bit as wondrous and enjoyable for the fully grown. The multi-year journey to publishing this poetry collection was an intensely personal one for Rosenberg’s daughter, Amy Losak, who tasked herself with continuing her mother’s literary legacy. When her mother died suddenly in 1996, Losak was mowed down, and subsequently, in the years that followed, overwhelmed by Rosenberg’s prolificacy: Her poems and submissions spanned a 30-plus-year career, and filled countless boxes that Losak now stores in her own attic and study.

Rosenberg was a public school teacher for many years in Kew Gardens, and haiku was her favorite medium. In the “Q” entry in H is for Haiku, Rosenberg writes, “Queuing for ice cream—sweat-sprinkled office workers on Queens Boulevard.” It’s the only haiku that specifically mentions Queens. And yet, you can feel the borough’s bustling pulse throughout the book’s alphabet— Xavier giving cuts at the beauty parlor, the green lobsters writhing like monsters in a fish window conjure Queens’ many fish markets, and the homeowners mating the covers of gusted trash cans could easily be Briarwood residents.

Losak, who spoke about the book by phone, said while there are no big messages or themes, “Quite a few poems in H is for Haiku reflect her urban surroundings—her life as a New Yorker, as a resident of Queens. And even though all of the poems are really old, they’re timeless and they’re fresh.”

Losak’s love for her poet mother is a layered journey that continues on. As she dug deeper into Rosenberg’s writing archives, she grew closer to the woman who raised her. She developed an even deeper respect for her mother, the artist, one of the first members of the Haiku Society of America, who had this lifelong, unrealized dream of publishing a book of haiku for children.

Losak said, “We always knew that my mother was creative and had a different way of looking at things and was intellectual in a very down-to-earth way. She had a keen eye—to use a cliché—she really did march to her own drummer and we loved her dearly, but I don’t know that we took that as seriously as perhaps we should have.”

In such simple and neat lines, Rosenberg translates her personality onto the page. It’s easy to picture her as Losak remembers—the woman who noticed things, who zeroed in on every detail, every sensation. The pair had a tradition of eating together at the recently shuttered Flagship Diner in Briarwood, a ritual that brought them ever closer in the last years of Rosenberg’s life.

“We would go and have these mother-daughter lunches,” said Losak. “A lot of times they prepared these humongous, heaping, wonderful salad platters. We would split the salad and that would be the meal for us. We’d get the chicken salad; if we were feeling more extravagant we’d get the shrimp salad. I was constantly, like, dashing around … but she liked to slow down and savor things. My mother would take her time. I could bolt down my food and be ready to leave in no time. She wanted to relax. Her hands would encircle the mug of coffee. It was as much about the feel of the mug as the coffee itself. It was as much about just—kind of relaxing and being in the moment as it was about the food.”

By book’s end, I felt that Rosenberg had whisked me around Queens and beyond—her lyrical haiku gospel converted me to an art form I’d never taken much prior notice of outside the classroom. With H is for Haiku, she continues to educate children and adults alike on the beauty and pleasure of short-form poetry in 5-7-5. (Of note: Rosenberg was not a dogmatic haikuist. Her alphabet haikus are neither strict about syllable count or subject matter. As the author herself said: “Haiku can’t be gimmicked; it can’t be shammed. If it is slicked into cuteness, haiku loses what it had to give.”)

H is for Haiku is about the moments we often overlook—the transportive experiences right in front of us, in our homes and neighborhoods—right here in Queens. Like Losak wrote in the book’s introduction, “Haiku poems make small moments ‘big.’”

H is for Haiku

Sawsan Chalabi | @schalabi.illustration

Haiku Society of America